In 2020, we experienced a major shift. Much of the world pitched in to limit the spread of the coronavirus, with people changing their daily routines to include a mixture of working from home, standing in socially-distanced lines, and awaiting local rules about what they could and could not do with members of different households.

It was a stressful and confusing time, and during it, cybercriminals adapted–sometimes a little too well.

Today, we’re going to talk about some of the most nefarious and shameful tricks we saw online in 2020. What we’re sharing is not a list of the most destructive attacks or the most serious–as that list would certainly be topped by the recent SolarWinds attack. Instead, this is a list of the cyberattacks and cyberattack techniques that surprised us, whether because of their near-imperceptibility, or because of their severe harshness.

These are the most enticing–or the most impossible-to-ignore–cyberattack lures and cyberattack capabilities of 2020.

Coronavirus, coronavirus, coronavirus

Beginning in February, Malwarebytes and many other cybersecurity researchers had already recorded a significant uptick in coronavirus lures being used to trick people into opening malicious emails and visiting dangerous websites.

First up, we found cybercriminals who impersonated the World Health Organization to distribute a fake coronavirus e-book. That attack vector must have worked, because in the same month, cybercriminals again impersonated the World Health Organization to spread the invasive keylogger Agent Tesla.

Other, similar efforts included impersonations of the non-descript “Department of Health” with pleas for donations, and reported Pakistani state-sponsored threat actors spreading a Remote Administration Tool through a coronavirus-themed spearphishing campaign. In fact, even the operators for the most-wanted cyberthreats Emotet and TrickBot switched up their lure language to focus on coronavirus.

We see this story during every major crisis: A panicked and confused public look for answers anywhere, including their inboxes. By taking advantage of this fear, threat actors are able to swindle countless victims who only wanted some guidance and clarity in their lives.

Tupperware credit card skimmer just one of many similar attacks

In the earliest days of responding to the coronavirus pandemic, local and state governments across the world began shutting down non-essential storefronts in an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19. While grocery stores and pharmacies remained open, other retail stores were sometimes forced to shift to an entirely online business model, since foot traffic became non-existent. This meant more stores selling more items online, and more people making their purchases on the Internet.

But where online shopping increased, so did attempts to steal online credit card data.

In March, Malwarebytes uncovered an active cyberattack against the food storage product-maker Tupperware. In the attack, threat actors managed to compromise Tupperware’s primary website by inserting a malicious code within an image file that would trigger a fraudulent payment form during the checkout process.

To unsuspecting users, the cyberheist was nearly undetectable. Upon trying to checkout from Tupperware’s online store, victims would first be shown a fraudulent, convincing payment form that asked for their credit card number, expiration date, and three-digit security code.

After victims confirmed their credit card details, they then received a warning notice that the website had timed out, and that they had to enter their credit card details a second time. Though this second payment form was actually legitimate, it was too late–the cyberthieves already had what they wanted.

The Tupperware attack was just one of many similar attacks in 2020. In fact, in March alone, we recorded a 26 percent increase in credit card skimming attacks compared to the month earlier. And February itself wasn’t a quiet month, as we also found threat actors hiding a credit card skimmer within a fake content delivery network.

Emotet blends into the crowd (of email attachments)

In 2020, one of the most devastating cyberthreats seriously improved its camouflage.

For more than two years, a dangerous malware called Emotet has proved to be one of the biggest threats facing businesses across the world. That’s because Emotet, which began as a banking Trojan, has evolved into a sophisticated threat that often serves as a first step into broader and longer-lasting cyber damage.

For most businesses today, an Emotet attack is no longer just an Emotet attack. Instead, a successful Emotet attack can go undetected for days or even weeks. In the meantime, threat actors can use Emotet to download a separate banking Trojan called Trickbot, and yet another ransomware called Ryuk.

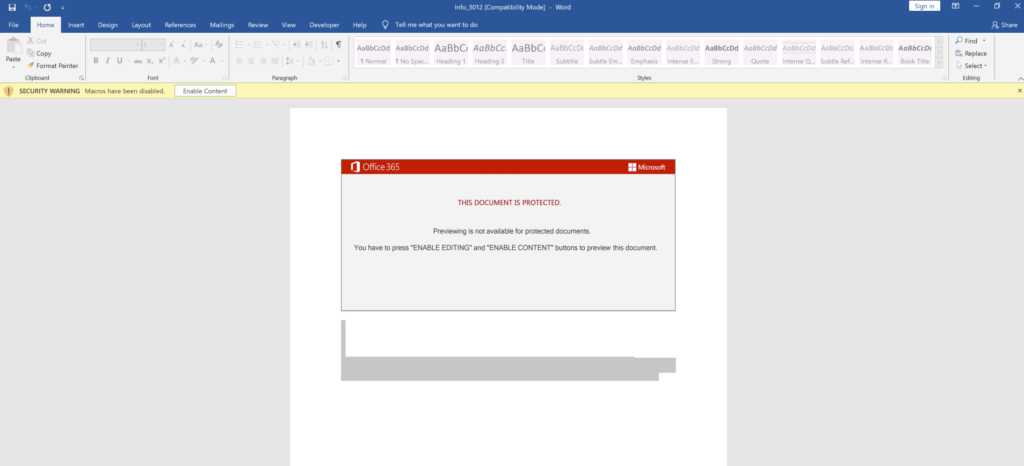

Making matters worse is that, over the years, Emotet has become increasingly hard to spot on first read. The banking Trojan is primarily spread through malspam, which are malicious emails that contain dangerous attachments like macro-enabled documents or other dangerous links. While similar malspam efforts are easy to detect, like the one-off billing invoice from a never-seen email address, Emotet is different.

In roughly one year, Emotet found a way to not only insert itself into active email threads, but to also copy and re-send legitimate email attachments so as to hide its own malicious payload amongst a set of documents that an email user may already recognize.

In tandem with implementing these new techniques, Emotet also came roaring back in the summer. Months later, it also received a superficial facelift, lurking within in a fake Microsoft Office update request.

We don’t know when we’ll finally be rid of Emotet, but we know that day can’t come soon enough.

Ransomware grows fond of extortion

In November of last year, a security staffing firm based in Pennsylvania faced an impossible deadline. They had just been hit with a ransomware attack, and, in one of the first documented cases at the time, they were given an option: pay the ransom, or your confidential files get leaked online for everyone to see.

This was the work of the so-called “Maze Crew,” operators behind the Maze ransomware.

In Pennsylvania, the clock was ticking, and the Maze Crew began to signal that it wasn’t playing around. Using an email address connected to Maze ransomware attacks, someone from the Maze Crew emailed a reporter at Bleeping Computer and basically bragged about their attack. In their email, they wrote:

“I am writing to you because we have breached Allied Universal security firm (aus.com), downloaded data and executed Maze ransomware in their network.

They were asked to pay ransom in order to get decryptor and be safe from data leakage, we have also told them that we would write to you about this situation if they dont pay us, because it is a shame for the security firm to get breached and ransomwared.”

We gave them time to think until this day, but it seems they abandoned payment process.”

The security firm refused to pay Maze Crew’s ransom, and, true to its word, Maze Crew released 700 MB of data and stolen files from the attack.

Interestingly, the operators behind Maze ransomware claimed in November that they were retiring. Whether or not they’re to be believed, the damage they’ve done is everlasting. Following that extortion stint they pulled last year, other threat actors followed suit. In fact, according to one report in August, 30 percent of all ransomware attacks now involves extortion threats. In 22 percent of attacks, threat actors actually take the first step in fulfilling those threats, having exfiltrated data from their targets.

If only threat actors didn’t look to other threat actors for inspiration.

Release the Kraken

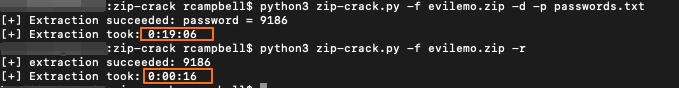

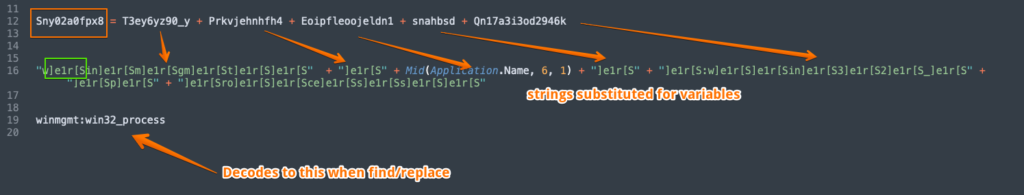

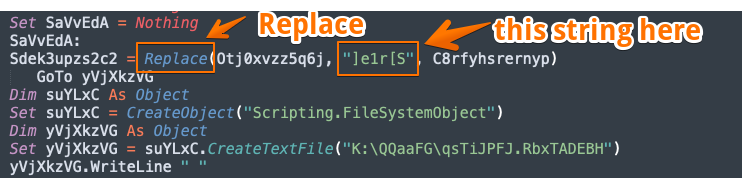

In October, our threat intelligence team published its findings on a cyberthreat that is as elusive and as slippery as its name: Kraken.

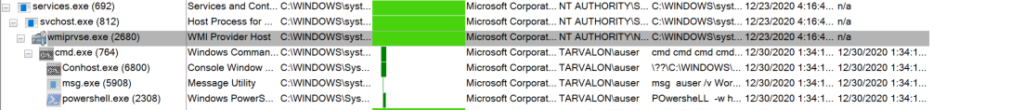

The attack first came through a malicious document–that was likely spread through spearphishing campaigns–that promised information about obtaining workers’ compensation. Opening the document enabling its content will then allow for a connection to “yourrighttocompensation[.]com” and it will result in a separate, downloaded image. Inside, a malicious macro starts a chain of events that loads and executes a payload from memory.

The payload is a .Net DLL that injects an embedded shellcode into the Windows Error Reporting service, WerFault.exe. But before the attack can actually trigger, the DLL performs a few, sly tricks to avoid detection. First, it checks for the presence of a debugger by measuring the time it takes to complete a certain set of instructions. Then, it checks for the presence of VMware or VirtualBox. It then checks for a processor feature, and the shellcode then also checks for a debugger. After one last, final debugging check, it creates its final shellcode in a new thread.

After all that work, the final shellcode in a set of instructions makes an HTTP request to download a malicious payload.

There is a bit of good news here, though. On further investigation, we found that this sneaky threat was not tied to any active APT group, but instead was the work of red team activities testing security.

Phew!

Imposter syndrome

In April, our team discovered that a group of threat actors had built a malicious website meant to serve as a gate to the Fallout exploit kit, which can distribute the Raccoon information stealer.

The method itself is nothing new, and threat actors build malicious websites all the time for just these types of attacks. What did surprise us, though, is the organization that the threat actors tried to impersonate: It was us, Malwarebytes.

The malicious domain, at malwarebytes-free[.]com, presented users with much of the same information on our own homepage, as that information was simply swiped and reposted.

The domain was registered on March 29 via REGISTRAR OF DOMAIN NAMES REG.RU LLC and was, at the time, hosted in Russia at 173.192.139[.]27. When we looked closer, we found a short piece of JavaScript on the copycat site that checked a user’s web browser. If the user was visiting the site on Internet Explorer, they would be led to a malicious URL which belonged to the Fallout exploit kit.

If these cyberthieves were trying to flatter us, it didn’t work.

A very long year

In 2020, not only did the coronavirus prove to be one of the most long-running lures to trick people into having their machines infected, but the capabilities of malware increased dramatically.

It isn’t all doom and gloom this year, though. Malwarebytes has done an enormous amount of work to keep you safe, and we’re constantly tracking what goes bump in the night to make sure you’re safe throughout the day.

Also, we shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves and judge all cyberthreats this year by the most alluring ones. In fact, tomorrow, we’re going to take a look at the strangest cyber events of 2020, and, spoiler alert, sometimes threat actors mess up hard.

The post The most enticing cyberattacks of 2020 appeared first on Malware Devil.

https://malwaredevil.com/2020/12/30/the-most-enticing-cyberattacks-of-2020-13/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=the-most-enticing-cyberattacks-of-2020-13